The Printer & the Machines

"Transitory" Inflation in the Age of Abundant Software

Disclaimer: this is speculative and I’m still noodling on it, but figured it is better to noodle out in the open and you help hone my thinking. Critiques are welcome. Not investment advice, etc.

MACRO HEAVY

There is no denying we are in a macro heavy investment environment. “Fundamental valuation” analysis has given way to a market largely dictated by the mercurial incantations of the Fed. Bad news is good, good news is bad. The key driver of asset performance is less actual performance and much more about the global denominator in which such assets are priced (i.e. dollar-based liquidity.)

Long-term debt cycle evangelist Ray Dalio is on record proclaiming the late hour of our current cycle. A ~70 year period of continual leverage built up in an economic system which will ultimately find a reckoning as individuals realize there are more “claims on assets” (i.e. debt or money) than there are underlying assets to be claimed. The three ways in which this “default” can occur are a restructuring (everyone takes a haircut), austerity (spending is reduced), or debasement (inflation runs hot, reducing the future debt burden by devaluing the currency).

Long-term Debt Cycle

Source: The Hatch Fund

Macro is challenging because of the quantum of significant variables: Astrology for the affluent, if you will. Late in a debt cycle, the challenge rises as traditional metrics are replaced by the unknowable, yet consequential decisions of fallible central bankers sitting in clandestine ivory towers driving an ever more unwieldy machine. The longer the music plays, the greater the consequences of mismanagement.

I am no macro guru. Particularly in the short term, palm-reading the machinations of the market is a talent few have been proven to possess. The chart readers, the liquidity watchers, the Fed interpreters - 10% investors, 90% infotainer. The sharks do not spend time on social media.

However, when the noise gets to a fevered pitch, sometimes it’s helpful to step back at a high level and use simple frameworks to weigh the main variables.

Below is a highly simplified, non-quantitative framework to examine the inflation-deflation debate. The Nobel-worthy seesaw framework :)

The Esteemed Seesaw Framework (VERY broad strokes)

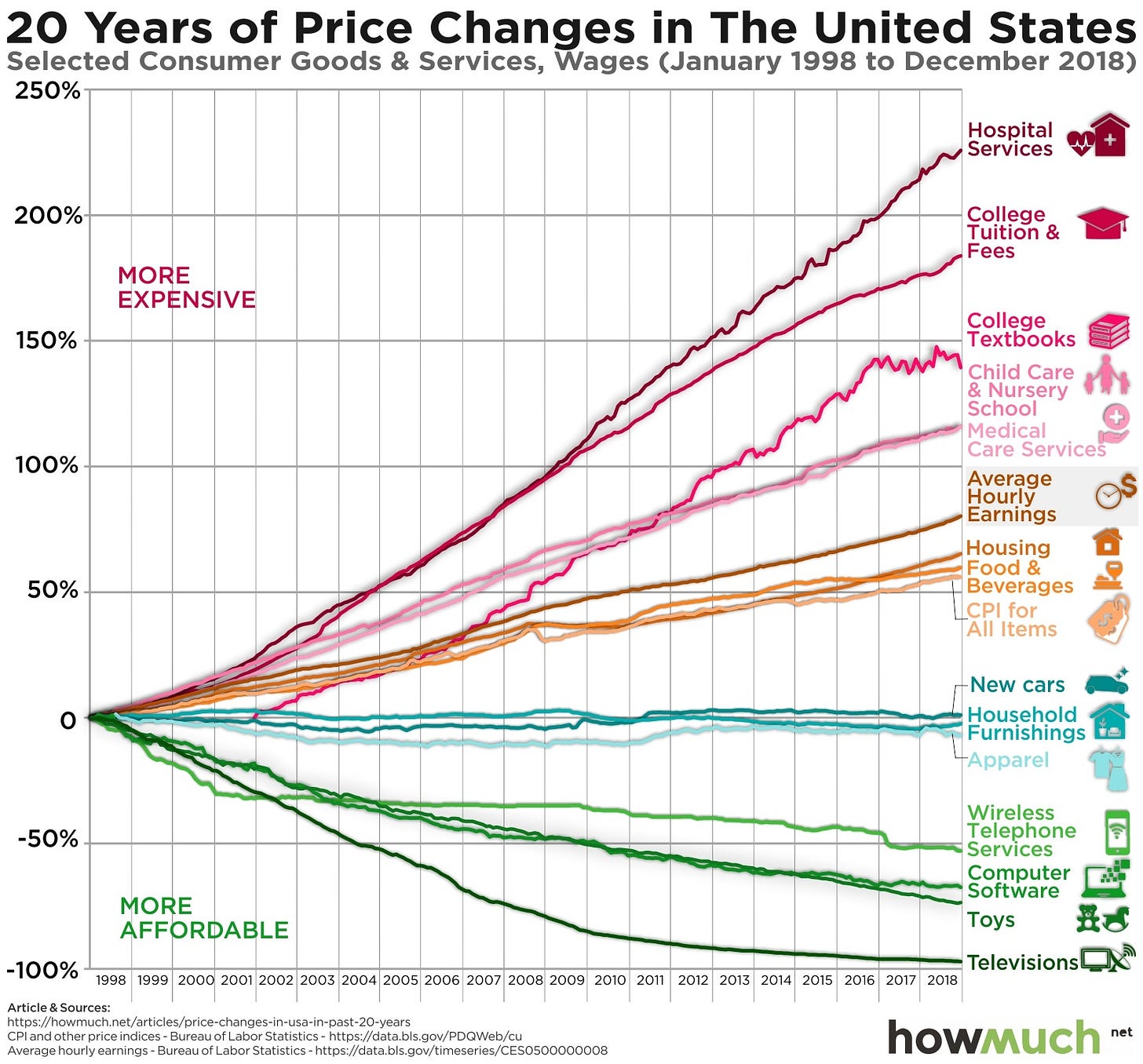

Post-1990, the global monetary regime was anchored by myriad disinflationary factors steadily dragging interest rates down following Paul Volker’s famous 1980s showdown with inflation.

The world was at peace under a U.S. hegemon. Free market ideology was traversing the globe, opening new markets for outsourcing and driving down labor costs. The PC revolution was underway, reaping productivity gains at the pace of Moore’s law. The internet - near free, instant communication without borders - had begun its ascent.

With such disinflationary tailwinds, even looser monetary policy proved unable to stir inflation. These productivity tailwinds would prove dominant all the way through 2020, including the GFC.

The subprime crash was another spectacular deleveraging event; a deflationary juggernaut stemming from U.S. excesses to hobble the global financial system, leaving an extended downturn in credit, earnings, and jobs in its wake.

The Quantitative Easing unleashed by Great Depression student Ben Bernanke helped to combat this spiral - potentially staving off a 2nd Great Depression - but at the cost of a Fed balance sheet and significant moral hazard introduced into the private markets.

However, to the surprise of many, the scourge of inflation was not unleashed in the wake of this sizable US$3.7 trillion intervention by the Fed. The prices of goods and services remained stable. Mainstreet’s demand remained muted. Excess liquidity flowed not into goods and services but into the price of assets.

After 2008, both bankers and investors became complacent.

Inflation had been “tamed” by a combination of demographics, process efficiencies, accelerating technology, and technocratic management. With such tailwinds, there would always be room for ample liquidity injection to combat the excesses of the business cycle in the face of any Minsky moments. The ensuing bull run was glorious, papering over any external shocks with cheap money.

S&P 500 Index

But all good things, including low-inflation regimes, must come to an end. To the surprise of many pundits, the weights of the seesaw shifted sharply during the pandemic.

With COVID, the size of the spending bazooka was astronomical, but the key misstep was a misdiagnosis of the type of crisis the pandemic had introduced. The bureaucrats were, as usual, fighting the last war - haunted by the spectre of another financially-driven deflationary collapse.

With COVID, many of the previous tailwinds driving productivity gains abruptly reversed. “Lockdowns” and shortages plagued global supply chains, highlighting inherent vulnerabilities - of both biological and geopolitical origins.

Compounding the problem, the U.S. government expanded beyond monetary policy (keeping interest rates low) and into fairly non-discretionary fiscal policy (PPP + Stimmies) at the exact same time supply-chain shortages emerged. To be fair, what else can you do when individuals are stuck at home without work? The supply-demand imbalance soon became obvious.

And then came the kicker. The nail in the coffin for an already deflated “team transitory” (sorry).

Geopolitical conflict emerged as a significant variable for the first time in 30 years as Russia invaded Ukraine, sending delicately constructed global energy markets into a tailspin. The conflict spooked markets into a further examination of the rising tensions between the U.S. and China, accelerating the “decoupling” narrative across both public and private investors - an expensive undertaking.

Upon realizing its misdiagnosis, the Fed had no choice but to slam on the breaks. Hard.

Today, we are tilting from inflationary to disinflationary quite aggressively as demand is crushed by the Fed’s aggressive tightening cycle. The impact is just beginning to bleed out into the real economy via the wealth effect, the real estate freeze, and a regional banking system paralyzed by Fed inflicted duress.

However, financial intervention aside, the secular trends are no longer as one sided as they had been for 30 years prior.

Sure, the disinflationary tailwinds are not negligible. Digitization / automation continue their relentless march. Aging demographics will weigh on consumption. The AI productivity bomb has only just begun. However, the counterweights of geopolitical conflict and the green transition are also only just beginning to be felt.

Conflict is always inflationary. Thirty years of efficiency optimization reversed in short order: a new regime of “resilience” requiring greater domestic investment, a reorganization of supply-chains, increased military spending, and revamped infrastructure to re-shore lost capabilities. This is all happening at the same time global governments have committed to a green transition which will cost US$9.2 trillion annually through 2050 (US$275 trillion in estimated aggregate expenditures to reach net zero).1

Source: McKinsey: The net-zero transition

These investments are all capital intensive.

And the borrowing to undertake such large investments will now be happening at 5% as opposed to near 0%; all in highly indebted economies with fairly bleak growth outlooks.

The Cost of Free Money

It’s hard to argue with Stan Drunkenmiller - an investment icon boasting a 25 year track-record of ~30% returns - arguably the individual on the planet most in tune with the machinations of the market. Drunkenmiller is convinced of a hard landing, citing “11 years of free money, a broad asset bubble, and the Federal Reserve increasing rates by 500 basis points within 12 months”2 as “unprecedented”.

He has compared the reckless pace of spending in the U.S. to “watching a horror movie unfold”, citing the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates that seniors will account for ~100% of tax revenue by 2040 and if future entitlements are taken into account, the U.S. debt burden is closer to US$200 trillion, far more than the official US$31.4 trillion limit3. Simply put, the situation is looking dire and something will have to happen to the money spigot.

The above color Drunkenmiller’s assertion of a “high probability” the stock market is flat for the next decade; a stark departure from the up-and-to-the-right markets we have grown accustomed to over the past decade.

For the first time in decades, the Fed’s hands will be tied by the structural forces listed above with any lack of resolve carrying the risk of a second inflationary spike and a rebuke from the bond vigilantes. Because of this, the Fed will almost certainly error on the side of caution, steering the economy into a near-term recession.

However… and I say this very timidly… I can’t help but seeing the outlines of a bizarre Deja Vu; a replay of the last four decades played on 3x - 4x fast-forward in the decade ahead.

While painful, inflation will be brought to heal (likely by a recession), the great infra investment cycle will not last forever, and continued gains in automation will reintroduce deflationary tailwinds offsetting increasing expenditures.

This will once again provide central bankers with leeway to spend, driving liquidity back into the market, debasing the denominator, letting inflation run a bit hot to ease the debt load, and boosting asset prices with corporate profits less saddled by pesky labor costs.

In my opinion, we will emerge from 2020s pointedly in the age of capital. An age defined by automation driven productivity and a politics of redistribution.

THE AGE SOFTWARE ABUNDANCE

One of the most insightful pieces I’ve read recently is “Societies Technical Debt and Software’s Gutenberg Moment” by Sk Ventures.

What does a world look like in which the cost of producing software drops precipitously?

A world in which software development dramatically expands from a specialized, expensive few to anyone capable of manipulating natural language?

LLMs (large language models) have advanced quickly to serve as a sort of “meta compiler” between natural language and code, similar to the way a coding language is compiled into the 0s and 1s which laisses with the microprocessor. With the rise of this new meta compiler, the price of software development will plummet, rapidly expanding production.

What if the pace of new software deployed will now directly follow the exponential jumps we have seen in computation capacity?

Source: OurWorldinData, BothFleshandmore.com

What impact will this have on Baumol’s cost disease?

What happens when the cost curves underpinning micro-electronics begin to infiltrate other, traditionally higher cost service-oriented industries with automated intelligence?

This will be a massive deflationary shock.

THE AGE OF CAPITAL. THE AGE OF POLITICS

I could be wrong, but my base case is a choppy ~24 months followed by a market realization that the acceleration of AI’s gains is likely to outstrip other, more inflationary inputs. With the pace that AI has moved the last 6 months, it seems probable we will have ubiquitous, cheap intelligence by the end of the decade. A productivity bomb to dramatically outpace the outsourcing and telecommunications boom of the post 90s era, driving down costs, and uncuffing Central Bankers once again.

The tug-of-war would then resume: Automation vs. the Money Printer.

If this hypothesis is true, the implications should be clear. First, similar to the last three decades, owning assets - and higher risk assets at that - would be the best way to preserve or enhance purchasing power (assuming regulations / politics remain in their current status quo). The printers will be on, interest rates would come down, and the liquidity in which assets are priced once again expanding.

However, just as many investors this cycle have learned that the “market” is subordinated to policy of central banks, during the next cycle investors will learn the market is subordinated to politics. Decisions made in the halls of congress, the chambers of parliament, or the compound at Zhongnanhai will increasingly dictate ultimate after-tax returns. The disruption caused by AI will drive unparalleled efficiency gains, but also unparalleled displacement and public rebukes of the “invisible hand”.

Interestingly, policy makers have set a course where easy money will be difficult, if not impossible to turn off. These manipulations of the market have furthered inequality leading to social unrest. This social unrest will be accentuated by technological acceleration. The outcome will be an appeal to the same policy makers to step in to redistribute the manipulated gains which they engineered in the first place. I guess there are two ways to say it… both ending in the same place.

In a world of abundant software, money will be cheap. In a world of cheap money, assets go up. In a world where assets go up, inequality widens.

In a world of abundant intelligence, labor is displaced. In a world of displaced labor, returns to capital increase. In a world where returns on capital increase at the expense of labor, inequality widens.

In a world of rising inequality, outcomes will be decided increasingly by politics...

Perhaps the only realm more difficult than economics to predict.

Yahoo Finance “Drunkenmiller Interview: 10 Key Takeaways”

Business Insider: Interview with Stan Drunkenmiller

Great to have the Durian back!