The Elephant & The Dragon

India, China, and the Shifting Winds Atop the Himalayas

Disclaimer: these views are my own and do not reflect those of any organization or entity. Also, shoutout to my man Asian Charts for the feedback and injecting many interesting factoids in the final sections.

Photo Source: Zhang Yun, China-US Focus

“A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history when we step out from the old to the new when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance”

- Jawaharlal Nehru, “Tryst with Destiny”

In international investment circles, the tangible cooling on the Chinese market and the counter enthusiasm surrounding the subcontinent is palpable. In normal times, such “consensus” signals would make my spidey senses tingle: a contrarian signal to hone my near-term focus on Chinese names. The Fed hiking cycle, the Chinese internet crackdown, the lockdowns, the “decoupling” narrative, and growing political and governance concerns for international capital in the world’s second largest economy combine to suggest attractive entry points in some generational Chinese companies. For any remaining skeptics of the Chinese tech ecosystem, I recommend a visit to Tsinghua University in Beijing: the ambition, creativity, and work ethic I witnessed during a recent visit are truly world class.

However, an objective view of the landscape betrays not just temporary dislocations in price or sentiment, but large, structural changes in the tectonic plates underpinning the global economy. A very real “regime change” birthed of geopolitical and ideological realities which, for the first time since the fall of the Berlin wall, threaten to shift the currents of international trade.

China’s meteoric, yet stubbornly undemocratic rise within the existing world order, COVID’s revealed supply chain fragility, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have set the stage for a “reassessment” in capitals from D.C. to Moscow; Brussels to Beijing. History has rebooted.

This marks a significant turning point; a westward shift in the tailwinds sweeping down from the Himalayas.

China’s four decade growth miracle will not simply collapse as suggested by Peter Zeihan, but is likely to slow as previous tailwinds become headwinds. Demographics aside, the destination of new manufacturing capacity will no longer default to China. At the margin, governments, companies, and investors are actively assessing their geopolitical exposure, and because of China’s successful integration within global supply chains over the last three decades, many international firms now find themselves over-exposed. This will weigh on Chinese growth.

It’s equally massive neighbor to the southwest is the logical beneficiary of this diversification. For too long, India has been held back by its lack of manufacturing prowess: it’s historic suspicion of international investment, unwieldy bureaucracy, underinvestment in infrastructure, and the gravitational vortex for FDI which has been modern China over the last thirty years, all frustrated India’s potential as a manufacturing powerhouse.

These headwinds are beginning to subside.

Is it now India’s turn to inflect? Will history look back from 2050 and tell a story of the India “go-go years” similar to post-1990 China? Why now? Why did China inflect first to begin with?

As always, a peak into the annals of modern history between the dancing giants can provide clues as to what may come next.

“Let some people get rich first”

- Deng Xiaoping

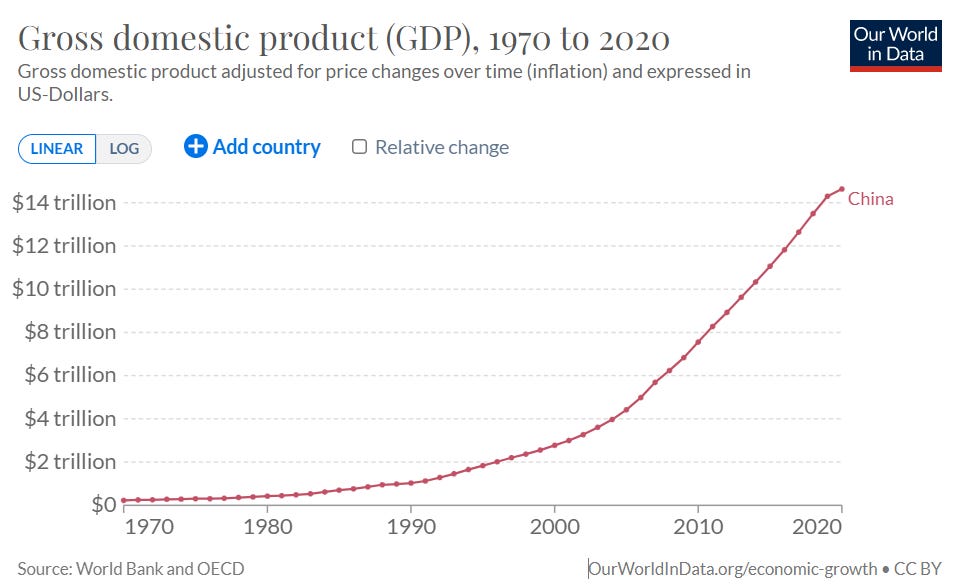

Why did China get rich first? How was it able to capitalize after the post-Mao upheaval to embark on the most miraculous economic run in history? To grow GDP from ~US$230b to US$15t (a >60x increase!!!) in under two generations, catapulting GDP per capita1 by >10x in the process?

Interestingly, India’s GDP per capita was higher than China’s up until about 1990 before the China growth story kicked into high gear, inflecting aggressively after the 2001 ascension into the WTO.

This is not to say India’s performance has been dismal. Since the liberal reforms starting in the early 90s, it’s ~5-6% growth over the period has been respectable, birthing greater urbanization and glitzy metropoles from Delhi to Bangalore, Mumbai to Kolkata, forcing open the narrow doors from desperate poverty to the budding sprouts of an aspiring middle class.

However, China’s performance has spoiled the curve; a growth miracle unparalleled in human history lifting >850 million people out of poverty. A combination of sound leadership, good policy, rural investments, hard work, and strategic integration into global supply chains provided the foundations for China’s meteoric rise.

But did it have to be this way? Was China always destined to be the “factory of the world”?

I would argue no. India missed a golden opportunity in the post-colonial decades to cement itself as a manufacturing hub - to establish its own ties with western markets and integrate with a globalizing world post-WWII while China struggled through the upheaval from the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

By the time India began correcting course in the 90s, the Chinese agglomeration effects had a 13 year head start. India has been struggling to catch up ever since.

“Time is not measured by the passing of years but by what one does, what one feels, and what one achieves”

- Jawaharlal Nehru

After winning independence from the British in 1947, India’s leadership was justifiably skeptical of outside interference. The rapid USSR industrialization story was in full swing, and founding Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru leaned towards socialism as the model to kick-start India’s post-colonial economic engine. This proved a significant misstep for two generations of Indians.

To be fair, Nehru had his hands full with much more than economic matters after India’s founding, consolidating a fragmented India into a unified nation. The tapestry of states, provincial princes, languages, religions, and customs which makes India so vibrant also makes the world’s largest democracy difficult to steer. After the British withdrawal and the chaos of partition with Pakistan, Nehru jumped from crisis to crisis - separatist movements in the east, conflict in Kashmir, disputes with dethroned princes, not to mention religious riots inflaming the country. Simply keeping India together, under a secular constitution, was a heroic effort. The fact India has remained democratic defied almost all expert opinions going back to partition - a testament to the truly unique story that is modern India and the political leadership of Nehru.

Still, in hindsight, Nehru’s economic policies - focusing on self-sufficiency, state-led investment, and capital-intensive public works - proved a substantial drag. In the post-WWII years, the playbook for rapid economic growth was visible along the Pacific rim. From Japan to Korea, Taiwan to Singapore, land reform, integration within global supply chains, opening to foreign direct investment, all while protecting and subsidizing local champions disciplined through export controls, drove impressive rates of growth in much of East Asia in the decades after WWII.

A formula China was to study closely in the late 20th century.

Sadly, India was slower in its economic enlightenment. Post-Nehru, growth was further frustrated by his daughter Indira Gandhi who oversaw the continued centralization of economic policy. Indira Gandhi’s reign witnessed nationalization of the banks, various caps on private business, high tariffs, barriers to international trade and foreign exchange, and the expansion of the Kafkaesque “License Raj” - a labyrinthian cacophony of permits and licenses which made doing business in India almost impossible. Skepticism of the outside world remained, discouraging external investment and shunning global supply chains in favor of “self-sufficiency”, failing to galvanize the abundant lower cost labor so in-demand from a newly rich and globalizing west.

While India writhed in economic malaise, a mummy of self-inflicted red tape, China was throwing off the shackles of its own ideology and policy missteps of the Mao years. The consequences did indeed “shake the world”.

“It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice”

- Deng Xiaoping

After the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping was restored to power, deftly navigating a charged political climate, to embark on the famed era of “reform and opening”.

To summarize much, the era was marked by:

Economic liberalization with the planned economy gradually replaced by market oriented reforms (from ~12k → 1.5m private enterprises from ‘78 - ‘90)2

Agricultural reforms allowing farms to keep and sell surplus production (boosting grain output from 305m tons in 1978 to 407 million tons in 1984)3

Special economic zones to attract investment and foster export-led growth (most famously Shenzhen)

Decentralization of decision making power - providing more provincial decision making power (empowering local officials)

Throwing open the Doors to Foreign Direct Investment (from $3.5 billion in 1990 to 333 billion in 2021)4

The policies worked. After laying foundations in the 80s, the reforms began to show results. The promise of a large domestic market and a massive pool of affordable labor sucked money in like a blackhole - with an initial inflection visible in the early nineties (~13 years after reforms had begun).

India, similarly, had to wait for ~13 years for a noticeable inflection in FDI after the liberalizing market reforms under Dr. Manmohan Singh in the early 90s, doing away with some of the worst excesses of the License Raj.

Foreign Direct Investment (US$ in Billions)

Source: Worldbank FDI data

The reforms under Deng which sparked this FDI boom catalyzed an agglomeration effect: FDI boosted exports, more exports bred expertise, expertise attracted more FDI and around we went. In short order, it seemed all global supply chains had a foothold in China; a foothold which turned into a crater after entry into the WTO.

Exports of Goods and Services (US$ in Trillions)

Source: WorldBank Export Data

In both of the above charts, we see India is ~15 years behind China; (coincidentally?) roughly the same gap in their respective shifts towards more market friendly policies. After its early lead, China has maintained its strangle hold as the world’s global manufacturing hub, while India has been forced to substitute by exporting services.

The big question now is: will India finally begin to see an inflection in FDI and goods-based exports to kickstart its own agglomeration effects on the elusive manufacturing-led growth ladder?

If so, large shifts might be underway. The rise of China has been the biggest geopolitical and economic development of the last 30 years.

Deja Vu?

“Dream, dream, dream. Dreams transform into thoughts and thoughts result in action”

- Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, 11th President of India

Based on purely economic factors, the answer would be “no”. As highlighted by Ying Chen at LKY School of Public Policy, global manufacturers do not simply look for “the lowest cost of labor” but instead seek “labor productivity and cost-effectiveness” per unit of output. Due to various inputs, including pre-reform era policies directing public health and education to rural areas, China’s life expectancy and literacy rates remain well ahead of India, yet to even reach China’s 2001 level of development:

“Productivity can be affected by many factors, including labor quality, physical infrastructure, economies of agglomeration, and technology, in all of which India is currently lagging behind China”

- Ying Chen

Despite rising labor costs, the above combination of inputs has kept manufacturing capacity located in China with a stubborn ~29% of the total global manufacturing footprint calling middle kingdom home.

Yet, calculations are no longer purely economic. In the post-pandemic world, many companies including Apple, Boeing, Nokia, Ericsson, Samsung5 and others have announced increasing capacity in India - both to gain proximity to a large local market, but also to diversify their growing geopolitical risk. Is this the potential spark needed to propel India from a services powerhouse to a significant global power?

Whether or not India can capitalize on this golden opportunity remains to be seen. Infrastructure remains underdeveloped, climate change challenges are on the rise, pollution is already wreaking havoc, education is suboptimal, the Kafkaesque bureaucracy is far from dead, and ease of doing business remains a challenge.

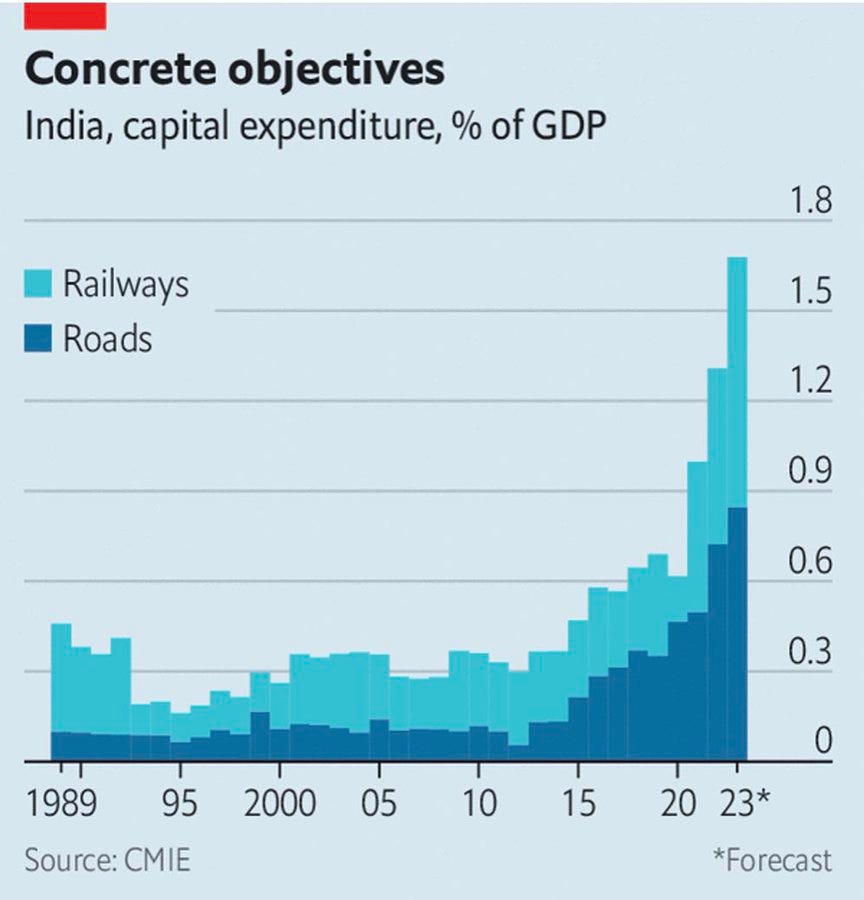

And yet, the Elephant is gaining momentum across many important metrics:

Ease of Doing Business: India has gone from ranked 142nd (out of 189) in 2015 to 63 (out of 190) in 2020 - a strong indicator of Modi’s seriousness in attracting external investment to India

Youth literacy jumped from 76% in 2000 to 92% in 2018

Life expectancy jumped from 62.5 years in 2000 to 70 years by 2019

Poverty rate: the percentage of the population living below $1.90 per day has declined from ~35% in 2000 to ~9% in 2019

Announced in 2014, the “Make in India” initiative also appears to be sprouting legs:

Production-linked incentive schemes are emerging in key industries

Infra spending is up significantly

A train transformation is underway - and yes, they are manufactured in house

The real estate boom in major Indian cities is well underway

Not to mention impressive gains in defense and space related industries

These production trends will be assisted by a large and growing domestic market. Despite the relatively low GDP per Capita, there are still 100m Indians with per capita income comparable to Mexico, China, or Eastern Europe. India is now the world’s third largest auto market and third largest aviation market; trends which signal its ascension on the world rankings.

If growth rates persist, India will surpass Germany and Japan in GDP by the end of the decade to become the world’s third largest economy.

“You can change friends but not neighbors”

- Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Former Prime Minister of India

And while the East Asian blueprint is quite clear, the world has changed much in the last thirty years. Automation in particular promises to make many supply-chains less labor intensive. Many western companies are keen to “near-shore” hubs closer to home. Advances in artificial intelligence promise to outpace “upskilling” efforts across the globe and soon will be integrated into robotics. The “demographic dividend” may yet turn out to be a “demographic liability”.

Still, automation will take time.

Last year, I wrote a fairly pessimistic piece called Deglobalization and the Developing World which I now recant somewhat. While the piece highlights real concerns, near-shoring can only go so far to contradict the laws of economics. For instance, the bloated cost structure will never allow for the building of trailing-edge chips in the United States despite its strategic benefits. However, geopolitical realities dictate investments will need to be made abroad to limit chokepoints by geopolitical rivals.

This is where India (and Mexico and Southeast Asia) has have a real shot and capturing some of the manufacturing share which has been soaked up by China in previous decades. A final push to get another 1.4b people on the road to manufacturing-led growth before the automation gap closes the door completely. To be fair, the confluence of factors which led to China’s rapid ascension is unlikely to be replicated, but a path between India’s current trajectory and China’s trajectory post WTO inclusion is very much in the cards.

China has stood up and gotten rich; a growth miracle which indeed “shook the world”.

After a winding journey, it’s giant neighbor to the Southwest appears to be stirring.

Good Reads

China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know by Arthur Kroeber

When China Rules the World by Martin Jacques

Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China by Ezra Vogel.

In Spite of the Gods: The Rise of Modern India by Edward Luce

India: A Portrait by Patrick French

Superfast Primetime Ultimate Nation by Adam Roberts

Will India Replace China as the New Global Manufacturing Hub? by Ying Chen

Here…comes…India!!! by Noah Smith

Adjusted for purchasing power between countries for better comparison. Worldbank. Our World in Data.

China Statistical Yearbook (1991)

Worldbank.

Worldbank.

Ying Chen, LKY School of Public Policy “Will India Replace China as the New Global Manufacturing Hub?”