Inflationary Decade, Deflationary Century

A Layman's Look at Inflation's Resurgence

Regime Change

Over the last two years, basically one question mattered to investment performance:

“Did you predict the resurrection of inflation in the wake of COVID and its persistence?

Given ~40 years of benign inflation, most experts were dismissive of the inflation “Cassandras”. Despite large amounts of QE, the inflation mongers after the 2008 financial crisis proved sterile. Deflationary forces ultimately won the day, leading to slow growth even on the back of accommodating monetary policy.

So, what changed?

Disclaimer: I’m not an economist, and macro is not my area of expertise. I, too, was caught off guard by the persistent inflationary shock and am using this essay as an attempt to understand why.

To many in the financial markets, the below explanations may seem obvious, but I still find it valuable to spell out what happened in plain English. Why this time was, in fact, different. And, in light of these facts, whether inflation will remain persistent or not and on what time horizon (clearly speculative). The trajectory of inflation is the singularly most important variable impacting the economy and investment returns and, to put it candidly, our ability to forecast its path is dismal.

I will timidly add my layman’s input to the literature and await my thrashing from the econ twitterati.

Unleashing the Ghost of Arthur Burns

Why, after a decade+ of quantitative easing and hefty deficits, did inflation raise its ugly head in 2021? Three culprits seem most likely:

The Global Pandemic (COVID) was a different kind of “shock”

Fiscal Stimulus (“Stimmies”) put $$$ in the hands of regular households

The Revenge of Geopolitics: Real Politik > Adam Smith

The potent combination of printing A LOT of money AND giving it directly to households WHILE a global pandemic crippled supply chains AND globalization’s fragilities were highlighted proved a blow too many for the Great Moderation, unleashing the ghost of Arthur Burns on an unsuspecting public.

COVID:

The pandemic was ultimately a different sort of “shock” than the 2008 financial crisis. 2008 was a financial crisis: a build up of unsustainable leverage - particularly within the US housing market - which culminated in a rapid deleveraging (an unwinding of loans & spike in defaults) igniting a liquidity crisis as banks withdrew risk from the economic engine in a desperate attempt to salvage their balance sheets.

This was a “demand shock”: a chain reaction of de-risking from banks, investors, businesses, and consumers where actors “tighten their belts” and withdrawal credit at the exact time it is most needed. Learning from the policy mistakes of the Great Depression, the Federal Reserve stepped in as the “lender of last resort”, making loans to unsteady financial institutions to combat the deflationary spiral in an attempt to “jump start” the economy with needed liquidity.

The pandemic was different. As opposed to a pure “demand shock”, COVID had a significant impact on supply. The two happened in sequence. First, as market sentiment collapsed in February 2020 with the virus’ global onset, a large demand shock ripped through the system leading Jerome Powell & Co. to counteract these forces via a US$5 trillion bazooka:

Source: New York Times - Where $5 Trillion in Pandemic Stimulus Money Went

The bazooka managed to stall the collapse in demand, but did nothing to assuage the impact of the virus itself. Lockdowns commenced, stores closed, factories went unmanned, and supply-chains grinded to a halt. The severe response measures in China in particular (the “factory of the world”) ensured supply shortages of many key inputs from raw material refinement to electronics.

This reduction in supply happened at the exact time demand for every day goods and services received heavy government subsidies.

“STIMMIES”:

Until the pandemic, monetary policy - the manipulation of interest rates - had been the primarily tool policy makers had used to either slow or stimulate the economy. By lowering interest rates to friendly levels and lending money to banks cheaply, the Fed hoped to reignite growth after the global financial crisis.

However, monetary policy is intermediated through the banking system and capital markets. Instead of loans flowing to individuals and SMEs, the artificially cheap money was used by Wall Street and Silicon Valley to promote aggressive expansion, consolidation, and share buybacks leading to a boom in tech and capital markets more broadly. As opposed to an increase in prices for consumer goods and services, asset price inflation was the primary consequence of easy monetary policy intermediated through the banking system.

Clearly, monetary stimulus was at work in the wake of the 2020 Bazooka. However, fiscal measures (i.e. government expenditures) also played a role including ~US$1.5 trillion in direct stimulus checks and unemployment benefits to households in need of everyday goods.

Source: New York Times - Where $5 Trillion in Pandemic Stimulus Money Went

Clearly, much of this funding was necessary to keep families afloat amidst forced closures of their livelihoods. However, as opposed to asset prices, the “stimmies” were primarily spent on everyday goods - groceries, rent, gasoline, etc. - at the exact same time the supply shortages were hitting the market.

So, demand for consumer goods and services got a massive $1.8 trillion injection at the same time new supply was stagnating.

Demand up, Supply down = Prices up.

GEOPOLITICS:

The last inflationary variable is the “return of history1”. Ever since the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, the U.S.-led world order has pushed new technology and free-markets to every corner of the globe. Factories were pushed offshore, tankers have grown to island size, China joined the WTO, and supply-chains have elongated in search of ever cheaper input costs. Telecommunications technology, globalization, and relative peace kept end-consumer costs down by letting Adam Smith's doctrine flourish globally, reducing labor costs and letting competitive advantage do its thing.

Blessed be the name of the market.

However, the pandemic highlighted the fragility of global supply chains. Suddenly, “resilience” trumped “efficiency” as the new supply-chain buzzword. Building “redundancy” gathered inertia as the U.S. - China “decoupling” rhetoric gained steam, and moved into hyper-speed with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. After lying dormant for 30 years, geopolitics reemerged to replace economics at the top of the global pecking order.

“National security” including “food security”, “energy security”, “military spending” and control over “systemically important” supply-chains are resurgent in policy circles. New nuclear plants, renewable farms, LNG terminals, battleships, and re-shored factories are… expensive. They will require high investment.

This will put upward pressure on inputs from energy, to labor, to core tech components. In a word: inflationary.

What happens now?

The Fed: Making Money Expensive Again

Inflation is weird because much of it is psychological. Clearly, the supply and demand imbalance play a large roll in an initial inflationary jolt, but whether inflation persists and for how long depends on how market participants perceive inflation. If, for example, workers see prices increasing at the grocery store, they will demand higher wages. If grocery stores see their wages (a key input cost) increasing, they will raise prices further on end consumers.

This is an inflationary spiral or in the words of the economic clergy: “an anchoring of inflation expectations”. This is bad. Price stability is a key input for commerce allowing individuals and businesses to plan ahead and invest in the future.

The Federal Reserve, with a dual mandate to promote price stability (i.e. benign inflation) and maximize employment, now has the unenviable task of stabilizing prices before inflation expectations become “unanchored”. This means getting (the formerly subsidized) demand back in line with the (still limited) supply. Without tools to impact supply, the only solution is to crush demand.

This means making money expensive.

By raising interest rates, the Federal Reserve dampens economic growth. Money to invest in new projects becomes more expensive. Mortgage rates rise considerably. Over-levered or less profitable companies can’t meet their obligations and are forced to cut costs (i.e. jobs) and stop investments which dampens consumer spending and future growth prospects.

In capital markets, liquidity is pulled “back down the risk-curve” towards lower-risk investments. Suddenly, US treasuries provide investors with attractive yields (from 0 to ~5% nominal). Given no new money is entering the system (actually the inverse), higher-risk investments in equities, growth tech, and crypto are sold aggressively to position the portfolio for the new credit environment of lower risk and higher yields. With the cost of money going up, the price paid today for distant future outcomes goes down considerably.

This is what we have witnessed in 2022.

How Much Pain, Sir?

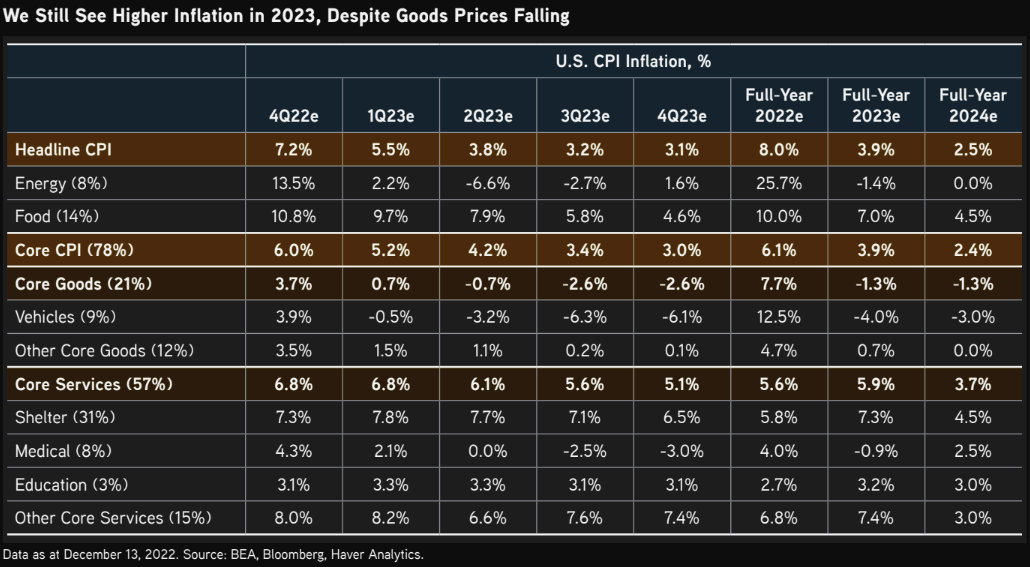

The good news is it appears the Fed’s medicine is having an impact. Growth is falling fast with inflation following in its wake, expected to fall to from 8% in 2022 to ~4% in 2023.

Despite making strong progress, the Fed is likely to keep rates fairly “elevated” (close to 5%) throughout 2023 to ensure the “taming” of inflation.

Source: KKR Global Macro

The Fed must thread the needle between:

a tight labor market (i.e. many older workers have opted for early retirement during COVID and demographic decline means there are less younger ones to fill their shoes) and

a housing market which cannot sustain rates above 5% for very long (people begin defaulting on mortgages = deflationary spiral).

It’s a tight rope, but it looks like the Fed has a path to achieving it. The more interesting question is where is the “resting heart rate” for inflation on the other side of this initial spike?

Most expect a higher resting rate than the previous decade’s 1 - 2%.

The Inflationary Decade Ahead of a Deflationary Century

My base case is the 2020s will be inflationary so the 2030s will not. Near term, central banks are intentionally sedating economic activity to contain the supply / demand imbalances triggered by COVID + STIMMIES. However, the third leg of the stool - nation states reasserting themselves over the global free market - will provide a floor on prices. The reshoring of supply-chains, greater investments in redundancy and self-sufficiency, a shortage of labor in developed markets, and an under-investment in energy create the set up for an inflationary “investment phase” this decade.

Even with the promising trajectory of inflation accentuated by the Fed’s resolve, very rarely is inflation a one hit wonder:

However, higher costs of energy and labor in the short-to-medium term will also force developed economies to invest heavily in automation to remain competitive. The investment phase should see spikes in many input costs, but the implementation phase may see significantly reduced marginal costs - both in terms of labor and energy - for future goods and services.

Think solar cost curves. Think the marginal cost of nuclear. Think driverless cars. Think chatGPT v8. Think preventive medicine. Think the inside of a Tesla Factory.

Not a lot of… people.

Eventually, the overwhelming deflationary forces of these technologies will win out. The first wave of cost reductions were built on a combination of automation and lower costs from globalization. With globalization slowing, companies and governments will double down on automation. Automation has high fixed up front costs, but low marginal costs of production.

Alternative energy is similar. Solar and nuclear require upfront investment, but variable costs are low. With the need for labor diminishing and energy inputs decreasing in cost, deflationary pressures will reestablish dominance.

The question is really one of time horizons.

NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE

My own (likely flawed) prediction is inflation will be tamed over the next ~2 years due to conservative federal reserve management leading to a volatile, yet recognizable recovery in asset prices. However, given the pressures of the investment cycle and the psychological “regime change” undergone by many investors, continued bouts with inflation in the decade ahead seem likely.

Keep in mind, central banks around the globe need partially-elevated inflation to help pay off their staggering debt-loads. Additionally, if deflationary forces do reassert themselves, policy makers have found a new, popular tool - fiscal stimulus - which is unlikely to fade into the background.

During those future inflationary bouts where the Fed is forced to pump the breaks, risk-assets crater. Then is the time to step in and buy your ticket to the future: synthetic biology, crypto-assets, artificial intelligence, nuclear fusion, etc.

Once the inflationary decade is behind us and the upfront investments are sunk, buckle up for an unparalleled deflationary age. A market boom to make the 2010s look small courtesy of another cheap money bonanza.

Until then, keep your head on a swivel :).

Reference to “The End of History” by Francis Fukuyama and the rising challenge of more illiberal forms of government to the liberal US-led status quo.