Digital Georgism

Economic Rents & Diverting the Road to Serfdom

Henry George and the Information Economy - just the fusion you had been waiting for heading into Easter weekend :)

This week, we explore:

The rising resentment towards capitalism in the West

Progress & Poverty: socializing economic rents

Digital Landlords: rent extraction in the 21st century

Potential remedies: policy or competition?

Universal basic income vs. distributed basic equity

Capitalism is out of favor in the West.

The engine that birthed the greatest gains in living standards in world history, reduced to a four syllable cliché and a bad after taste. The masses seeking asylum from the inequities of “capitalism” in the hallow promises of socialists and populists from both sides of the political divide. Who can blame them?

Despite the encouraging rise in global equality, within borders the picture is darker. Wages have stagnated. Growth is elusive. The share of gains to labor is in decline. And nationalistic sentiments are on the rise in response. The benefits of free markets, liberal ideals, and globalization have been reserved for a privileged few coastal elites.

However, many ills which have plagued “capitalism” in the 21st century are not free markets at all, but their inverse. Monopoly power masquerading under the guise of free market capitalism, tilting the playing field toward incumbents. A corrupted yield curve inflating assets at the expense of savings, a VC & tech industry built around winner-take-all economics, egregiously misaligned incentives in healthcare, unsustainable expenditures (stoking ~8%+ inflation), regressive tax policies, massive asset management oligopolies, and the pervasive extraction of economic rents. Some of these ills are due to misdirected government policy, others due to collusion, and other still to zero marginal costs of tech-enabled businesses.

Free markets are little more than free people making free decisions. Most people don’t hate free markets. They hate corrupt markets.

As accredited to Mark Twain: “history never repeats, but it does rhyme”. By standing on the shoulders of giants like Henry George we can peer back into the 19th century for clues in fending off monopoly excesses and restoring more just market structures.

Progress & Poverty: Socializing Economic Rents

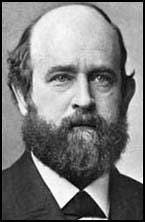

For the unfamiliar, Henry George was a well-known 19th century political economist best known for authoring Progress and Poverty (1879). Progress and Poverty was an instant success - outselling any other book in the 1890s with the exception of the Bible, catalyzing the progressive era of the early 20th century against the “Robber Barons” of the day - Rockefeller, Carnegie, Vanderbilt and the like.

In this magnum opus, George strives to explain why poverty persists amidst accelerating economic and technological progress in the late 19th century. With the industrial revolution in full swing, George was perplexed by the high correlation of technological gains and urban poverty which seemed to tethered to it. George’s critique eventually dialed-in on landowners. The landed cohort in rapidly urbanizing areas benefitted greatly from the development of others: educational services, public infrastructure, property developers, and the general agglomeration effects of cities.

People want to be near other people, businesses, ideas, and energy. The more robust the agglomeration effects of a dense city, the more a landowner could charge in rents despite adding very little marginal productive capacity himself.

Landlords represented the extraction of economic rents on otherwise productive members of society: property developers, entrepreneurs, laborers, retailers, etc. Speculation of land values generally kept pace or exceeded wealth creation from non-extractive ventures and ate into the profits of entrepreneurs and labor in the form of ever higher rents rewarding private individuals with wealth created by social forces.

This is all too prevalent in Hanoi or Yangon today where land in the city center rapidly approaches Manhattan p.s.f. prices despite the gap in economic development. Land values often foreshadow the coming economic boom.

George’s presupposition was the tax code had it backwards: the gains from private wealth creation were socialized via the tax system (income and sales tax) whereas the public gains from urbanization and public services accrued privately to landowners. The incentives were misaligned.

George proposed a single “land value tax” to tax landowners annually on the value of land which would replace taxes on production and labor and incentivize the most productive use of land against speculative squatters. The gains would be distributed to developers, entrepreneurs, and laborers in the form of higher take-home profits and could be re-invested in public infrastructure (further increasing the land value) or even providing a universal basic dividend to residents.

In this way, George sought to socialize the unmerited monopoly profits of landowners and push resources towards more marginally productive activities.

Digital Landlords: Rent Extraction in CyberSpace

While Henry George was writing in an industrial context, we can reframe his principles towards the information economy of the 21st century. Like the late 19th century, dominant business platforms have emerged with monopoly power. Ford, Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Rockefeller and the other industrialists thrived on anti-competitive acquisitions, vertical integration, political clout, and economies of scale; squeezing out competitors and reaping monopoly profits.

Today’s tech barons have achieved similar monopoly profits in a different manner - largely through online marketplaces. The most expensive real estate on earth is no longer 5th Avenue in Manhattan or Nanjing Lu in Shanghai. It’s pixels on the Google landing page.

Instead of the tens of thousands which grace central park south on a daily basis, advertisers on leading digital platforms can reach hundreds of millions of potential clients. By capturing demand, these platforms now benefit from the same agglomeration effects as land owners in 19th century cities. Suppliers and advertisers compete in an evermore expensive auction to reach customers - Google, Facebook, Alibaba, and Apple in the middle - levying increasing economic rents.

While creating spectacularly innovative products to kick-start the platform, the marginal utility is driven by the merchants or users themselves.

Big tech is the new landlord.

21st Century Remedy: Policy or Competition?

Unfortunately, legislators are still fighting the last battle. Historically, most monopolies have been supply-driven; like OPEC. Corner the market and name the price for the constrained supply. Tech monopolies are the exact opposite.

In a land of digital abundance, he who controls demand, controls the market. The key to controlling demand is to delight the customer. Most consumers are not hurt by increasing dominance of big tech. In fact, its often the opposite. Costs and delivery times continue to plummet while customer experiences improve.

Customers generally love the products which are often monetized indirectly.

However, if we squint, we can find a few structural issues which weigh on economic health:

Platforms ultimately extract increasing economic rents from suppliers leading to reduced innovation, less business creation, less choice, and higher prices to consumers in the long-run. For example, how many business models are not viable because Apple charges 30% on App Store transactions?

Counterfactuals are notoriously difficult to demonstrate but the cost of monopolies to economic dynamism is very real. The massive developer and user community which makes Apple such a compelling platform is being squeezed to the benefit of Apple shareholders who arguably - after providing growth capital to an incredible business - have moved from the productive to extractive stage in a company’s life cycle. The marginal unit of productivity is increasingly crushed by the landlord.

Platforms centralize economic gains to relatively few shareholders at the expense of workers, SME entrepreneurs and other ecosystem participants dependent on the platform for distribution

Similar to George examining his 19th century surroundings and wondering why accelerating innovation was paired with increasing inequality, we have to look at the wonders of Amazon 2-hr delivery or instant global communication with friends and wonder: why is inequality spiraling at the exact same time these magical applications are thriving?

Obviously, big tech is far from alone. Globalization, digitization, and loose monetary policy are also key drivers, but increasing economic extraction from the leading players which centralizes gains and reduces marginal experimentation does play a part.

Apple is slowly replacing Goldman sacks as the new vampire squid.

While politicians clamor to combat the power of big tech, what can really be done? Breakup Facebook into multiple social networks? Breakup Google into three different search companies? Breakup Amazon into multiple online retailers?

The obvious issue is network effects clearly suck liquidity to the largest, most efficient platform. It would only be a matter of time before network effects crowned another champion - the new digital real estate tycoon.

Universal basic income vs. distributed basic equity

The problem with universal basic income is three-fold:

1) People generally do not want handouts

2) The slippery slope dynamic is real, the incentives poor, and inflation is already running at >8% which disproportionately hits the bottom 50%

3) Income inequality is a much less stark issue than wealth inequality

Steve Schwarzman is worth ~US$35b, but has a base salary of ~US$350k. In order to build wealth, you need to have ownership.

And in an economy which is rapidly undergoing digital disruption, you need ownership in the right companies.

Unfortunately, many regulators have constructed well-meaning regulation which has restricted access to top investment trends by retail investors. As opposed to “protecting” retail, compliance costs have pushed the innovative startup ecosystem into the private markets, soaking up an increasing amount of capital and value accrual outside of the reach of everyday investors.

The opportunity cost has been large. Retail investors have been “protected” from investing in many of the giants of the last ~15 years until those companies are well into the tens and sometimes hundreds of billions in valuation.

Incrementally, capital markets are not only restricted by income level but are also restricted by geography with many of the world’s poorest unable to access equities in top performing companies - even if those companies are operating in their jurisdiction, competing with and extracting value from local SMEs.

Unfortunately, I have little faith in today’s legislators to craft a nuanced policy-based solution along the lines of a 21st century digital landlord tax, when just grasping the basic mechanics of these new business models seems out of reach…

I would suggest a reversal of policies which restrict investment in leading companies (i.e. accredited investor laws) to broaden the gains and encourage open competition.

The key to reducing monopoly power is more competition, not less. Well meaning regulation all too often further shields incumbents from the new wave of challengers.

Through this lens, I believe distributed networks provide the most serious challenge to today’s centralized tech giants. The rebrand from “crypto” to “web3” has really been on point.

Like any early technological paradigm, there are grifters who will take advantage of the hype. Projects abound which are less than savory, but that is a small price to pay for a global coordination mechanism built on transparent, opensource rails. A new version of the internet which is more difficult to co-opt by large sent seekers.

If George were with us today, I imagine he would be cautiously optimistic about the potential of crypto networks. As opposed to facilitating increasing rent extraction, crypto networks provide an opportunity to further “socialize” the gains of network effects to the communities who are responsible for their value-accrual in the first place. No community, no value.

Network effects are the 21st century agglomeration effects.

By limiting user lock-in, providing the ability to “exit”, and opensourcing much of the code, rent extraction of platform technologies can be reduced.

Is it perfect? Absolutely not. Is there a path to an improvement over the status quo? 100%.

In many ways, crypto is one of the last truly free markets on earth. Open to anyone with an internet connection without regard to color, age, income, or nationality. As a proponent of individual freedoms, I have a hard time arguing with why that should be discouraged.

While Henry George proposed a land-tax which would “socialize” the benefits of economic development beyond extractive land-owners, web3 offers a market-based solution to further distribute the gains of network effects online to active participants.

In a world where networks are rapidly outstripping hierarchies, limits on rent-seeking and broader ownership of the networks set to propel economic development in the 21st century strikes me as one of the only realistic alternatives to the current status quo.

If not, Progress and Poverty may unfortunately go hand in hand this century just like they did in the 19th.

I always learn something reading your work